More than a hundred years ago, one man saw that modern lifestyles were taking their toll on our wellbeing. Long before Zumba, Body Combat and Hot Yoga, he built and promoted a world-famous exercise programme. His name is more well-known than his unusual story, which starts in Germany in the 1880s.

The man’s name was Joseph Pilates, and he got a poor start in life. He was a sickly kid who was picked on by his schoolmates. He had asthma, bad posture, and rickets (giving him soft, weak bones). To make things worse, he lost the sight in one eye at the age of five – allegedly from a stone used by a bully.

Yet as a teenager, he was earning money by posing as a model for anatomy charts. How had he transformed himself? Inspired by an interest in the ancient Greeks, he developed daily exercises to improve his health and wellbeing. He took to the weights and picked up bodybuilding, wrestling, yoga, and gymnastics. He overcame his disadvantages with focus and discipline.

By 1912 Pilates was living in England, working as a circus performer, boxer and self-defence instructor. When the First World War came, he was interned with other Germans for four years. In later life, he explained that many of the ideas that made him famous came during this time.

Pilates was held at the Knockaloe farm camp on the Isle of Man. As the months dragged on, he saw many fellow prisoners slump into apathy, with little to do but stare at the walls. But he also noticed the local cats. Although they were nothing but skin and bone, they were still full of beans, springing after the local mice. Why were the cats in such good shape, while humans grew weaker?

Pilates had learnt to watch bodies. He saw the cats stretching out, over and over again, keeping their muscles in shape. So he began thinking about exercises that would stretch a human’s muscles. He shared them with those around him, and they began to do the exercises, too.

For a while he worked in the hospital, helping soldiers too weak to walk. He set up resistance exercises by fixing springs to the ends of metal bed frames. So even these patients could improve their strength and flexibility. Over the years, ideas like this made their way into kit that’s still in use in modern Pilates studios.

Many of Pilates’ soldiers actually ended their war in better shape than when it started. When the Spanish flu epidemic swept across Europe in 1918, legend has it that not a single man under his care died. That’s remarkable when you consider the poor living conditions of these camps, hit hard by the deadly virus.

Like so many innovators, Pilates soon headed for the USA. On the boat over, he met his future wife, Clara. They set up a new gym in New York, where his ideas became popular among those wanting precise control of their bodies. Joe and Clara welcomed dancers, actors and opera singers – people who wanted to get back from injuries or improve their skills. All were introduced to fearsome-sounding equipment like the Universal Reformer, the Wunda Chair and the Spine Corrector.

Over the years, the gym saw an eclectic mix of famous visitors, including Laurence Olivier and Yehudi Menuhin. Joe’s ego and energy were balanced by Clara’s compassion. Some say she was the better teacher, and her approachable style took off. It showed that ‘Contrology’ (as Pilates was then called) could be tailored to any level of health and fitness.

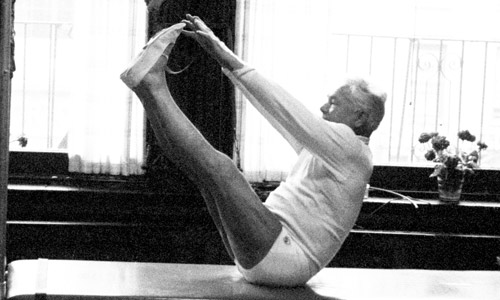

As Joe often told us, “Physical fitness is the first requisite of happiness.” He kept developing his methods until his death in 1967, a role model for energy, persistence, and health through exercise. There are photographs of him performing advanced stretches at the youthful age of 80. It just proves that there’s a lot you can learn from cats.