It’s not every day you learn a lesson from a Post-it note and a retired US Navy commander. But it happened to me last week. It’s a tale of leadership, and how to create places where everyone is thinking and engaged. That’s valuable in the military or the workplace, but it also has lessons for any group you’re involved in.

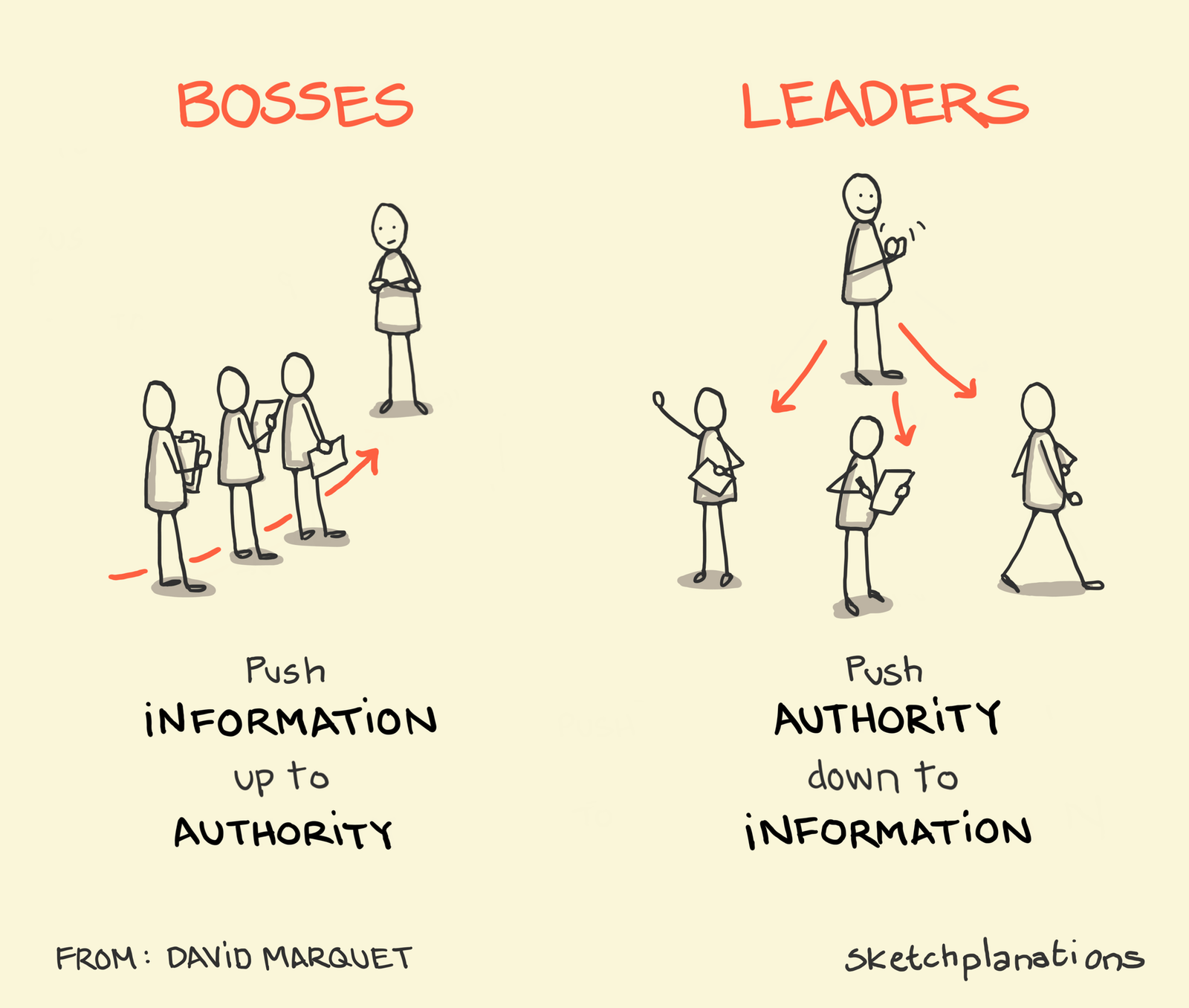

The Post-it that drew me in comes from the ever-wonderful Sketchplanations website. The image and caption made me stop and think:

“Bosses push information up to authority. Leaders push authority down to information.”

We’d all rather be called a leader than a boss, and most of us have some kind of leadership challenge in our lives. So I dug further to find that these were the words of a naval man called David Marquet. Twenty years ago, he ran an interesting social experiment.

The boss who knew everything

In the 1990s, Marquet was living his dream. After years at the Naval Academy he was now the captain of a nuclear submarine, the USS Olympia. For a whole year, he went back to school to learn about the ship. He memorised the wiring, the piping, how the pumps worked. He read about the crew and knew how they dealt with problems. He knew more about the submarine than anyone ever had, and was ready to give all the orders. Then something changed.

The fleet had another submarine, USS Santa Fe. It was the runt of the litter, with poor morale and performance. Other submariners knew it was the sub that never put to sea on time and couldn’t keep hold of its crew. When its captain resigned, Marquet was asked to step in – at two weeks’ notice. The USS Santa Fe was a very different type of submarine. What use was Marquet’s hard-won knowledge now?

His studying was now irrelevant. He couldn’t be the know-all leader he’d trained to be because he didn’t know it all. He couldn’t hide. After all, in a submarine, no-one is ever more than 200 feet away from the boss, day or night.

Around the same time, he’d started to question what he knew about leadership. His textbooks said it was ‘directing the thoughts, plans and actions of others.’ But he knew there was only one Obi Wan-kenobi, and that the rest of us can’t decide what other people think. In a world where he was no longer the know-all, he needed a new approach.

One event really brought this home. It was an exercise where the crew pretend the reactor is broken. They must power the ship on batteries – a bit like running a car on an electric toothbrush. When they shut down the reactor there’s a race. Can the crew solve the problem before the battery is drained?

During the exercise, Marquet asked an officer to speed up, using the battery faster. The order was passed on, but the speed stayed the same. A young crew member explained that, unlike other classes of submarine, theirs had only one speed under battery power. Marquet asked the officer if he’d known this. Yes, he had. So why had he passed on the order? “Because you told me to.”

Marquet realised that they were in a bad way. His lack of knowledge did not mix well with a crew that expected to follow orders. On a nuclear submarine, that was risky. At a meeting, he said that he’d trained for a different ship and needed them to be more proactive.

A young sailor chipped in. “No captain, it’s you. You need to be quiet.”

These days Marquet jokes that “perhaps this kid hadn’t seen too many submarine movies.” But an inner voice made him give it a try. He told the crew that (bar launching a missile) he was never going to give another order on this ship. He didn’t know what it was going to look like, or how it was going to work.

Pushing authority down

Marquet soon saw the advantages in working this way. He looked for more opportunities to push authority down to those with the best information. To apply for vacation leave, for example, a submariner had to use a form that went through six levels of sign-off. Yet his team leader was clearly the best-placed person to manage this. Empowering the crew to own more decisions was a great way to flatten the hierarchy and get stuff done.

How language changes culture

For their part the crew agreed to stop bringing the captain problems without solutions. They stopped saying “I recommend…” or “I’m thinking about doing this”. They switched to “I intend to…” and Marquet would nod and ask questions.

He realised how important language was in changing his crew’s culture. In a debrief after a fire drill he noticed a pattern in people’s responses. He was told that ‘they’ “didn’t pressurise the hose” or “were too slow.” Even among a hundred submariners, a ‘them and us’ tension had developed. Marquet fixed this with an easy-to-remember rhyme – “There’s no ‘they’ on the Santa Fe.”

One day an engineer came up to him with some bad news. He was about to explain that a pump repair would be delayed because the supply team ordered the wrong part. But he remembered he couldn’t say ‘they’. ‘They’ had to be replaced by ‘we’. And by saying ‘we’, the crew re-wired their brains. They started thinking of each other as one team, with no boundaries.

What happened?

David Marquest says it took him 10 years to figure out what really happened on the USS Santa Fe. He sums it up by saying they created leaders. Officer after officer was promoted to command their own ship. Inspections reported that the crew had the most powerful culture of teamwork ever seen in the US Navy. One year, 35 out of 35 submariners re-enlisted, when once it had been just three.

What can we learn?

For me, Marquet’s experiment is a classic case study in teamwork, culture and motivation. You may think you can control people, but this is a short-term fix. To really succeed, you must be happy saying, “I don’t know.” You need to build leaders around you – so their skills and energy can be applied to their workplaces, families, schools and communities. You have to create an environment where people can do what’s needed, without being told.