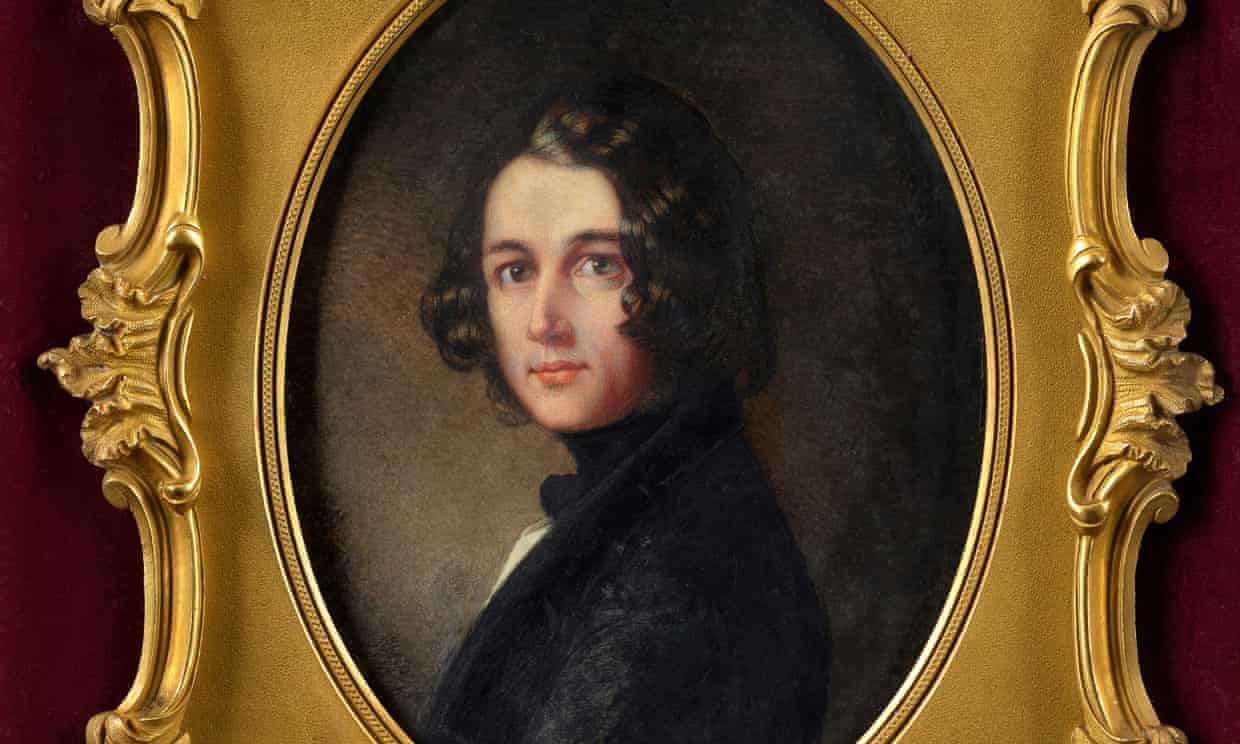

Two years ago I read about an extraordinary event in Pietermaritzburg, South Africa. At auction, a local man paid around £30 for a tray of bits-and-bobs. These included a small, faded portrait. About to throw it away, something told him not to. It turned out to be the famously lost painting of a young Charles Dickens, missing for over 130 years.

You might think this is just one of those charming stories that pops up now and then. But it’s interesting to look a little deeper. The painting was done in London in 1843, the year Dickens wrote his most well-loved novel. It’s a portrait of a man younger and more energetic than the bearded gentleman we’re used to seeing.

Every day Dickens’ eyes would take in the streets of London. Remarkable changes in recent years had made the city the richest and largest on the planet. Immigration saw the population soar, with living conditions for many beyond description. Rivers ran with filth, and medical care was basic and limited to the few. If you looked up from the street, the air was choked with sooty fog.

The famous book he wrote this year is, of course, A Christmas Carol. It tells the story of Ebenezer Scrooge, an elderly miser who cares for no-one. Scrooge is visited by the unhappy ghost of Jacob Marley (a former business partner), and the spirits of Christmas Past, Present and Yet to Come. The ghostly night softens him into a kinder, gentler man – not just at Christmas, but for the rest of his life.

It’s a story that’s always been popular and never out of print. Readers are drawn to sympathetic characters like Tiny Tim, whose family can barely support his needs. Dickens shows us how the poor were treated in Victorian London, and how a selfish man can redeem himself through warmth and generosity. He reminds us to take more notice of the lives of those around us.

Part of his genius was to see that he’d reach more people with a deeply-felt story. For years he’d been a letter-writing machine, campaigning hard for children’s rights, education, and other social reforms. But a story can sometimes be more ‘true’ than any number of letters, essays and pamphlets. It would give him a wider audience. This included the illiterate poor, who paid to have episodes of his other novels read aloud.

Dickens was appalled at how working-class people lived. Earlier in 1843, he saw first-hand the awful conditions for children in the Cornish tin mines. Closer to home, he spent time at one of the ‘Ragged schools’ set up to support the capital’s illiterate and half-starved street kids. He could see that impoverished children were turning to crime, and that learning could provide a better life.

His anger stemmed from his own childhood, too. As a youngster, his father was sent to a debtors’ prison. So young Charles had been forced to leave school and work at a dirty and rat-infested factory. He understood what happens when society ignores the poor, especially children. The Poor Laws of the day fueled his rage, as the workhouse system delivered extra misery to those least able to cope.

Nearly two hundred years later, we have related challenges to grapple with. It’s clear that the current pandemic is driving both poverty and inequality, as did disease and pollution in Dickens’ lifetime. Like today, these had a bigger effect on those at the bottom of society – acting like a tax on the poor. Those with the fewest resources always suffer most from poor health and job insecurity.

Driven by his message, Dickens raced to get the book done in six weeks, just in time for Christmas. That included long night walks of up to 20 miles, “when all sober folks had gone to bed.” The good news is that it’s only a two-hour read. If you can dig out a copy, you’ll feel further echoes down the generations, because so many parts of a modern Christmas are linked to this period.

Dickens was writing when the British were exploring old traditions like carols, and starting new ones – such as Christmas trees. The first commercial Christmas cards appeared in the week his book was published. A little later a confectioner, Tom Smith, invented a clever new way to sell sweets and called it the Christmas cracker. As the book became popular, it fuelled enthusiasm for Christmas and helped to spread the traditions we enjoy today.

Several phrases from the book are still going strong. “Merry Christmas” was used long before A Christmas Carol, but the book made it popular. It also introduced us to “Bah! Humbug!”, and of course everyone knows that a “Scrooge” is a miser.

Something that often surprises people is that the first collection of carols was only published in the 1830s. Just as the singing of carols spread joy, it’s said that Dickens called his story A Christmas Carol because he expected it to bring people together. It certainly did – there was nothing better to bring out the spirit of Christmas, and there’s nothing better now.

Dickens was a master of observing real life and reflecting it through stories. So although Ebenezer Scrooge was fictional, his traits of greed and ignorance were common among the privileged. Through him, Dickens showed that having empathy for problems like poverty was more noble than simply blaming the poor.

Scrooge is the best example we have of someone who realises it’s never too late to change. Whether sudden or gradual, deciding to take action is key, with small changes chained together delivering significant achievements. That’s something we can apply to every challenge we have in our modern lives. In the words of Scrooge’s creator, “A very little key will open a very heavy door.”

I re-read A Christmas Carol every year to remind myself how I can improve in the year ahead. It’s a good way to honour Christmas, and aim for a generosity of spirit and understanding all year round – as Scrooge learned to do.

There are many excellent film versions. If you don’t have the peace and quiet to read the book, why not watch one of my favourite three with family or friends over the holidays? I promise you won’t be disappointed.

Find out more:

Film: A Christmas Carol (1951)

Film: The Muppet Christmas Carol (1992)